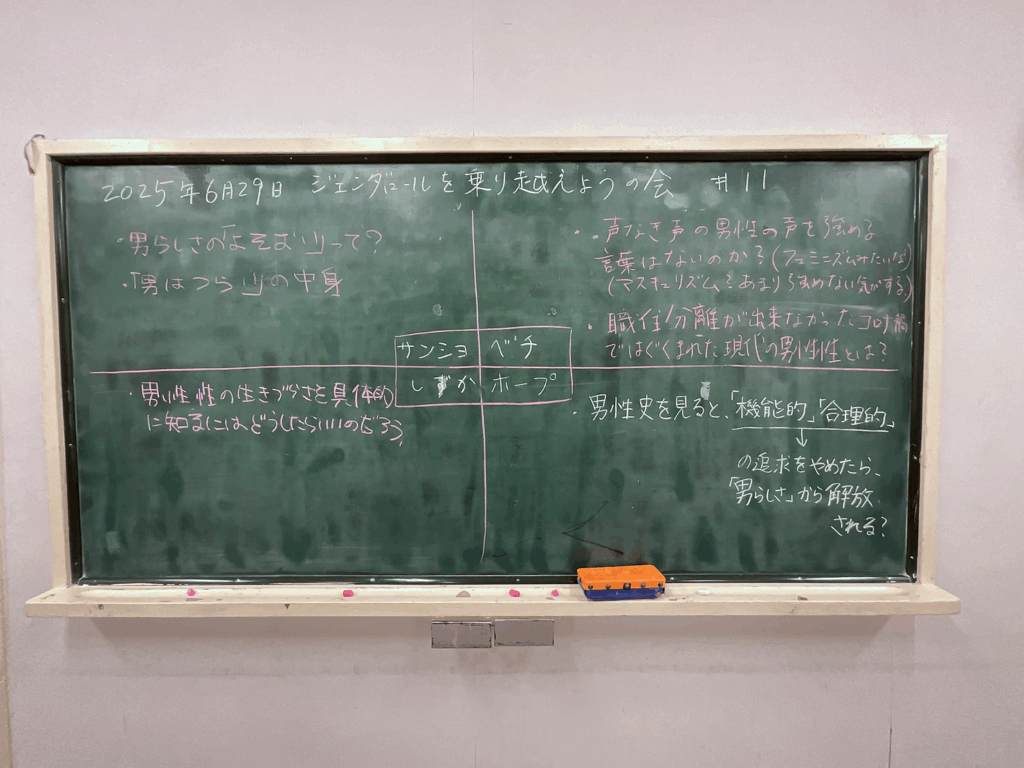

Session 11

June 29, 2025

Participants: 4

Overcoming Gender Roles

「Expanding the Range of Masculinity」

In this eleventh session of our study group on overcoming gender roles, we read and discussed Chapter 5, titled "Are All Men Strong?", from An Introduction to Western Gender History: From Family History to Global History by Naoko Yuge.

Taking “masculinity” as our theme, we engaged in a conversation about how images of men have shifted across nations, time periods, and cultures. We reflected on how men who fell outside the socially accepted mold of masculinity may have been rendered invisible, slipping through the cracks of recorded history.

Masculinity and Structures of Power

"The Patriarch and the Gentleman"

In our discussion of Japanese ideals of masculinity, terms like teishu kanpaku (authoritative husband), nihon danji (the quintessential Japanese man), and Kyushu danji (man from Kyushu, often stereotyped as tough and traditional) came up. These words evoked images of dignified, dominant male figures. One example was the traditional scene in which a wife asks her husband, “Would you like a bath or dinner first?”—a model that reflects a patriarchal household dynamic. At the same time, comparisons were made to the British "gentleman" figure. While the gentleman may appear kind and considerate, it was pointed out that both archetypes ultimately reflect a structure that objectifies women.

"Masculinity as an Expression of Power"

We also discussed how definitions of masculinity may have been shaped to reinforce the authority of the state or religion. One example was the historical existence of castrati—boys who were castrated to preserve their high voices. In an era when women were barred from participating in sacred rituals, these boys, with their angelic voices, sang in choirs. This practice symbolized the state’s power to regulate and control the body itself.

Similarly, in earlier eras, men’s fashion often included lace, necklaces, and other ornaments—used as expressions of status and power. Just as today some women enjoy wearing lace while others do not, participants questioned whether men in the past also had greater freedom and diversity in expressing their masculinity.

Masculinity and the Lines We Draw

The discussion eventually turned to the boundaries and lines society draws around masculinity.

For example, the practice of castrati—once accepted as a norm—was later deemed ethically problematic and eventually banned. This shift illustrates how societal standards of what is "right" or "acceptable" can change over time.

In the same way, television programs that were widely popular in Japan’s Showa era are now criticized for being sexist. These shifts suggest that changing societal norms have begun to bring previously invisible problems to light.

One participant shared a personal story: when someone commented that their son was "a mix with a Yamatonchu," they were suddenly made aware of the social boundary between Okinawan and mainland Japanese identities—something they had never consciously considered before. This experience highlighted how we often draw unconscious lines between categories such as man and woman, normal and other. Reflecting on these invisible lines can help us critically reexamine what we mean by "masculinity."

Words and Images That Unravel Masculinity

So how can we give voice to those who feel discomfort or dissonance living under traditional expectations of masculinity? During the discussion, one idea that emerged was that individuals who question the male roles imposed by society can open up possibilities for new forms of masculinity by sharing their own experiences and images.

"Expanding the Space for Masculinity"

One participant pointed out that the range of socially acceptable masculine expressions is surprisingly narrow. While commenting on women’s appearances is often considered taboo, remarks toward men like “You should work out more” or “You should lose weight” are commonly accepted.

This suggests that aspects of masculinity that fall outside the conventional frame are more likely to be criticized. The limited flexibility of what is considered “manly” may contribute to the discomfort many men experience. It was suggested that expanding the range of acceptable masculinity could help ease this sense of restriction and difficulty.

Participants also questioned why scholars who advocate for women’s rights—such as Yoko Tajima, Chizuko Ueno, and Raicho Hiratsuka—are widely known, while those who speak to men’s struggles remain obscure. Some felt that voicing these issues doesn’t necessarily lead to a more livable life for men—and may even carry a social cost. This fear or sense of futility might explain the relative silence.

The group also discussed the challenges of fostering genuine diversity. Expressing understanding or support for diversity does not always translate to true respect for difference. For instance, some people may “out” someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity without consent, thinking they are showing support. This kind of outing, though often overlooked among younger generations raised on diversity education, can still be harmful—especially across generations where levels of understanding differ. The conversation highlighted the need for greater awareness and care in how diversity is acknowledged.

Looking for a New Word Beyond “Feminism”

These conversations led to a shared recognition that masculinity is not a biological certainty, but a socially constructed image. Acknowledging this opens the door to imagining freer, more diverse ways of being a man.

This also raised the question of language. While feminism has been a powerful tool for voicing women’s issues, it also carries negative connotations for some—being seen as “loud” or “difficult.” As a result, many people hesitate to identify as feminists.

There was also mention of the difficulty men face in aligning with feminism, despite being sympathetic to its values. Although terms like masculinism or masculinist exist, they are not widely recognized or embraced in Japan. Participants felt that developing a new vocabulary or framework is essential to better represent men’s experiences and struggles.

"Heroes and Expanding Male Archetypes"

Finally, the group reflected on how male heroes in media have changed over time. From the stoic masculinity of Showa-era figures like Mito Komon or Otoko wa Tsurai yo, to the emotional and cooperative dynamics in modern franchises like Dragon Ball, One Piece, or Spider-Man, the model of masculinity has evolved.

More recent portrayals of heroism often feature teamwork rather than lone warriors. Likewise, the princess narrative has shifted—from being saved by a prince to celebrating relationships like sisterhood, as in Frozen. These cultural shifts in storytelling may also help reshape and expand our collective image of what a man can be.

Notes: Danshiro

References:

"A Beginner’s Guide to Western Gender History"

Written by Naoko Yuge

Chapter 5: “Are All Men Strong?”

This book is a valuable introduction to how gender has been constructed across Western history, offering insight into how these ideas can be deconstructed and reimagined today.

Past posts

- 植民地支配とジェンダー

- 軍事史とジェンダー

- Expanding the Range of Masculinity

- Body Image Through the Lens of Body History

- How History Shaped Our Ideas of Gender

- Gender Representation from the Perspective of Women’s History

- Exploring the Family of the Future through Family History

- Body, Feminism, and Porn

- Nation and Gender

- Choices in Labor, Sex Education, and Gender

- On Postmodern Families and Gender

- On Diversifying Families and Children's Rights

- Gender Roles in Parenting