Session 12

Sunday, July 20, 2025

Participants: 3

Overcoming Gender Roles

“Military History and Gender”

In this twelfth session of the Study Group on Beyond Gender Roles, participants read Chapter 6, “Is Being a Soldier ‘Being a Man’? — New Military History,” from An Introduction to Western Gender History: From Family History to Global History by Naoko Yuge.

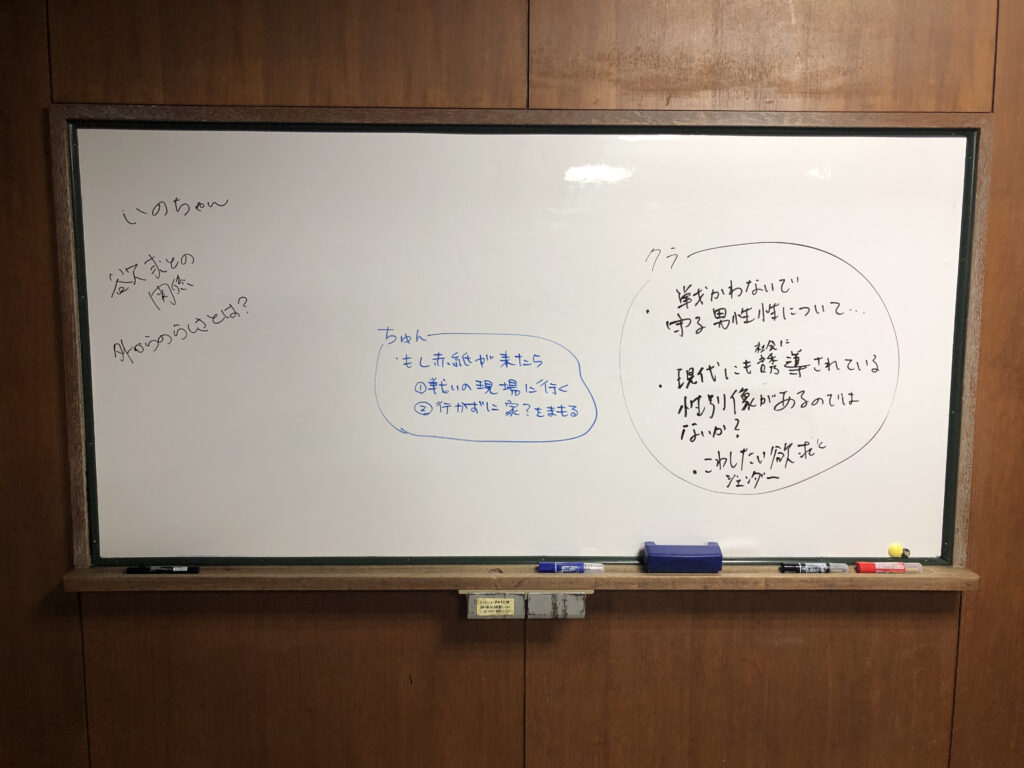

The group exchanged views on the kinds of “gendered expectations” that are demanded in the context of war.

Appearance and Gendered “Expectedness”

The discussion began with how participants relate to gendered expectations that arise from appearance. One participant shared that they were often perceived as a “soft” or “effeminate” boy, and in response, deliberately wore a hoodie with the word “Martial Arts” written in large letters in order to project a stronger image. By concealing the contours of their body, they tried to appear more powerful. This experience was shared with the group.

Hairstyles were also discussed, particularly the expectations imposed by society and workplaces. Participants shared differing views on whether to conform to such expectations and how to respond to them. One participant noted that when men grow their hair long, they are often told things like “Why don’t you cut it?” or “Tie it up,” and that letting one’s hair grow as a man is not an easy choice.

Another participant shared that because of their appearance and height, they were often placed at the very front during childhood events. From appearance alone, they were perceived as “a small, cute girl who is unlikely to be attacked,” illustrating how assumptions are imposed based solely on outward looks.

The Warrior Expected in Business

It was shared that in response to appearance-based expectations of gendered behavior, people may choose to comply, deliberately deviate, or simply endure and move past them, depending on the situation.

When hearing the word “fighting,” many people imagine the military. However, participants noted that in business settings, books that use war as a framework are often read as teaching materials for business strategy.

While there are many ways of fighting, it was suggested that in business contexts, “offensive strategies” are often regarded as masculine, and that men are implicitly expected to possess such qualities. Through this discussion, the image of men as inherently combative or warlike seemed to emerge beneath the surface.

The conversation developed from the juxtaposition of the extreme phrases “the sex that gives birth” and “the sex that kills,” which are often used to describe women and men respectively. From there, the group asked the reverse question: what might it mean to speak of “men who give birth,” metaphorically or otherwise?What does it mean for a way of fighting to be considered masculine? What does it mean for a way of fighting to be considered feminine? From these questions, participants discussed whether forceful, aggressive styles of fighting are automatically perceived as masculine, and whether fighting in order to protect something should be seen as unmasculine.

Ultimately, participants shared the view that aptitude for fighting and styles of combat do not seem to be determined by gender. There are women for whom offensive strategies are well suited, and men whose dispositions align more closely with protective or supportive forms of engagement.

The group discussed that the roles implied by terms such as “the sex that fights” and “the sex that gives birth” might originally be far more flexible, and that they could be assigned more freely according to context and suitability rather than fixed by gender.

Women and Soldiers — The Sex That Kills and the Sex That Gives Birth

Participants noted that contemporary warfare does not always require physical strength, as there are many forms of remote combat today. One participant remarked that “there are now many situations in which physical strength is not necessary for fighting.” Examples included drone operators and units engaged in cyber warfare. As technology advances, modes of combat have changed dramatically.

Nevertheless, broad gendered images—such as “men as the sex that fights” and “women as the sex that gives birth”—still seem to persist, even in business contexts. Historically, during times of war, men were assumed to become soldiers, while women, positioned as the sex that gives birth, were kept away from the battlefield. One participant mentioned having watched a documentary showing that many military units during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are composed of female soldiers.

An exhibition currently being held in Tokyo titled War and Clothing was also discussed. The exhibition includes examples such as dresses modeled after military epaulettes, demonstrating how military design elements have been incorporated into women’s clothing. Through these exhibits, participants sensed how women—who were not permitted to fight—had nonetheless worn the “aesthetics of the military” through fashion.

During the discussion, the topic of “impulses to destroy objects due to frustration” also emerged. While acknowledging that men are more often perpetrators in cases of domestic homicide, participants questioned whether anger and destructive impulses can truly be divided neatly along gender lines.

戦争動員におけるジェンダー操作

Soldiers did not gather naturally. Historically, states employed various social strategies during wartime to guide ordinary citizens—particularly men—toward feeling pride in enlisting.

In the early eighteenth century, armies were sometimes regarded as collections of social outcasts, and ideals of masculinity were not yet strongly associated with soldiers. As states recognized the need to transform the military’s low social status, processes emerged in which masculinity and the image of the soldier became strategically linked and emphasized by the state as wartime systems developed.

Cultures were formed that glorified soldiers as heroes and promoted masculine norms within the military that valued strength, loyalty, and silence. These methods differed by country. For example, in Germany, Hitler enhanced the appeal of enlistment through the design of attractive military uniforms. In Britain, social shame was used as pressure to encourage military service, such as the practice of giving white feathers to men who refused to serve.

Notes: Danshiro

References:

"A Beginner’s Guide to Western Gender History"

Written by Naoko Yuge

Chapter 6: “Is Being a Soldier ‘Being a Man’? — New Military History”

This book is a valuable introduction to how gender has been constructed across Western history, offering insight into how these ideas can be deconstructed and reimagined today.

Past posts

- Why the Trouble?

- Matrilineal Society, Instinct, and Gender

- Perspectives on Marriage in Japan

- Future References

- Gender Roles Considered from Article 24 of the Constitution

- Colonial Rule and Gender

- Military History and Gender

- Expanding the Range of Masculinity

- Body Image Through the Lens of Body History

- How History Shaped Our Ideas of Gender

- Gender Representation from the Perspective of Women’s History

- Exploring the Family of the Future through Family History

- Body, Feminism, and Porn

- Nation and Gender

- Choices in Labor, Sex Education, and Gender

- On Postmodern Families and Gender

- On Diversifying Families and Children's Rights

- Gender Roles in Parenting